Coolfood Pledge: Collective Member Progress through 2023

More than 70 food service providers have committed to Coolfood’s science-based target—known as the Coolfood Pledge—to reduce food-related emissions by 25% by 2030. If all Pledge members achieve this target, their reduced annual emissions will equal 5.2 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (tCO2e) — comparable to taking approximately 3.4 million cars off the road. [1]

Each year, Coolfood measures collective Pledge member progress toward the 2030 target using procurement data. It also provides cutting-edge behavioral science strategies that food service organizations can put into action to shift demand toward plant-based foods and achieve greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reductions. This report presents Coolfood Pledge members’ progress through 2023. [2]

![24_GRAPH-coolfood-2023-pledge-progress-report_table1 (2) (1)[41] Table 1: Changes in GHG emissions per plate by sector through 2022](https://coolfood.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/24_GRAPH-coolfood-2023-pledge-progress-report_table1-2-141.png)

After analyzing the data, it’s clear that, on average, all sectors are reducing their per-plate emissions and starting to make the necessary shifts in procurement. Cities and health care facilities continue to make the most significant progress toward the 2030 target, building off their progress in 2022 and setting an example for what can be achieved and how to do it. However, four years after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, many food providers in all sectors have seen business recover, or even expand; as a result, absolute emissions are on the rise. Despite the increases in recent years, absolute emissions are still currently on track for 2030 this year but will need to start decreasing again in 2024 to remain on track in future years. With just five years until 2030, members across the board must accelerate their shift toward low–carbon, plant-based foods.

All sectors have reduced per-plate emissions, with some sectors progressing faster than others

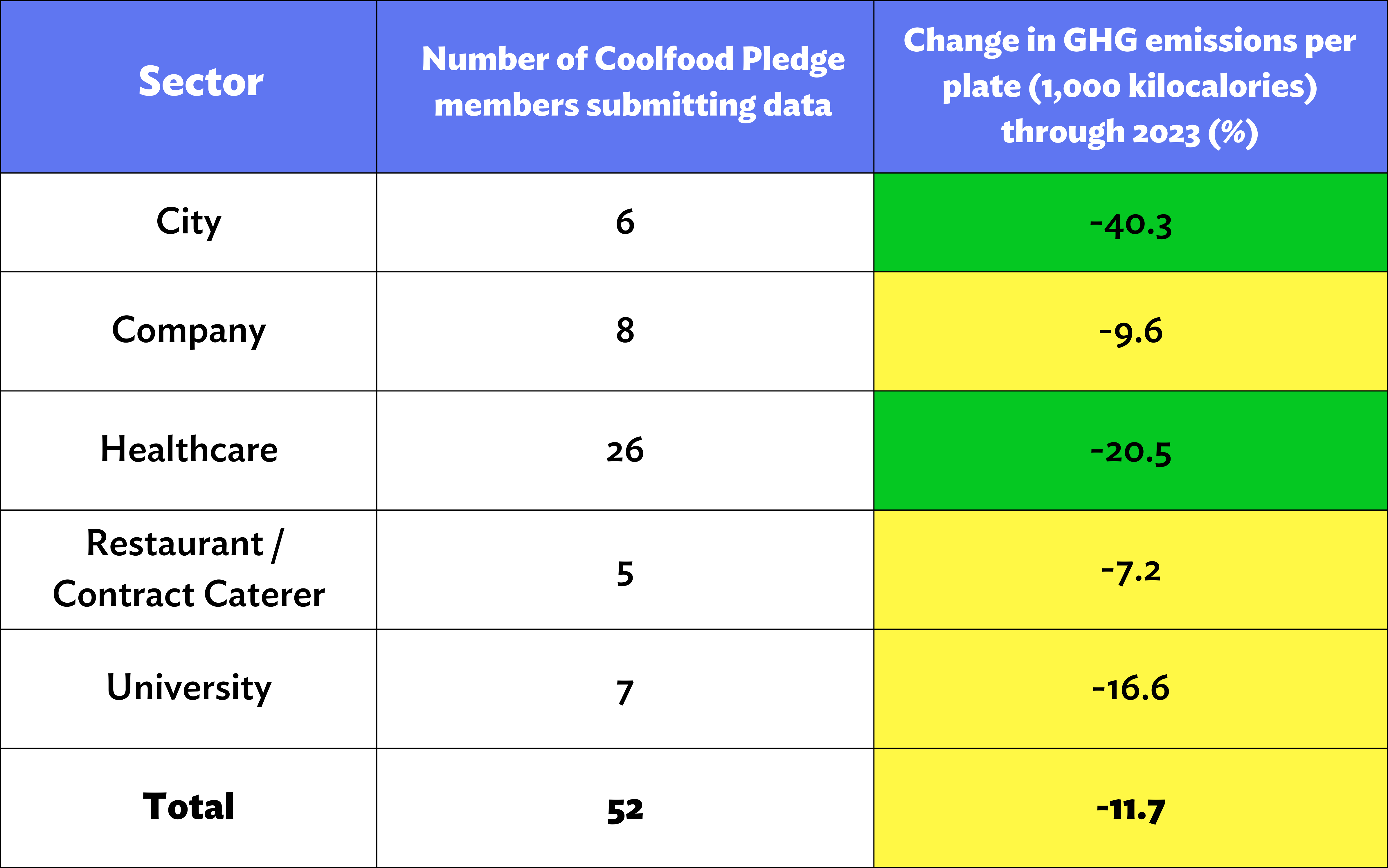

In 2023 we began analyzing sector-level progress toward the 2030 target. Table 1 looks at how each sector is performing based on these latest figures. Some Coolfood Pledge signatories (e.g., cities, contract caterers) serve food in multiple types of operations (e.g., schools, universities, government agencies, etc.); members are analyzed according to the entity that signed the pledge rather than where the food is served. The sector-level data reflects the achievements of the 52 members who joined prior to 2023.[3] Collectively, they serve more than 2.3 billion meals every year. Table 1 excludes members who joined the Coolfood Pledge in 2023-24 because they have not had sufficient time to implement changes that can be reflected in data through 2023.

As in previous progress reports, this report also includes the group’s estimated reduction of GHG emissions “per plate” through 2023. [4] The Coolfood Pledge includes a subtarget of a 38% reduction in emissions per plate by 2030.[5]

Table 1: Changes in GHG emissions per plate by sector through 2023

Notes: Trends shown for active members who joined the Coolfood Pledge prior to 2023. Reductions highlighted in green are ahead of the pace needed for 2030, whereas yellow indicates moving in the right direction but not at the right pace; through 2023, a minimum 20.3% reduction would be considered on track.

Sources: Member data; Poore and Nemecek (2018) (agricultural supply chain emissions); Searchinger et al. (2018) (carbon opportunity costs).

All sectors — including cities, companies, health care facilities, restaurants and contract caterers and universities — are moving in the right direction by reducing their “per–plate” GHG emissions, with the total cohort achieving an overall 12% reduction in per-plate emissions. Figure 1 compares each sector’s progress in reducing per-plate emissions over time.

Figure 1: Changes in GHG emissions per plate by sector over time

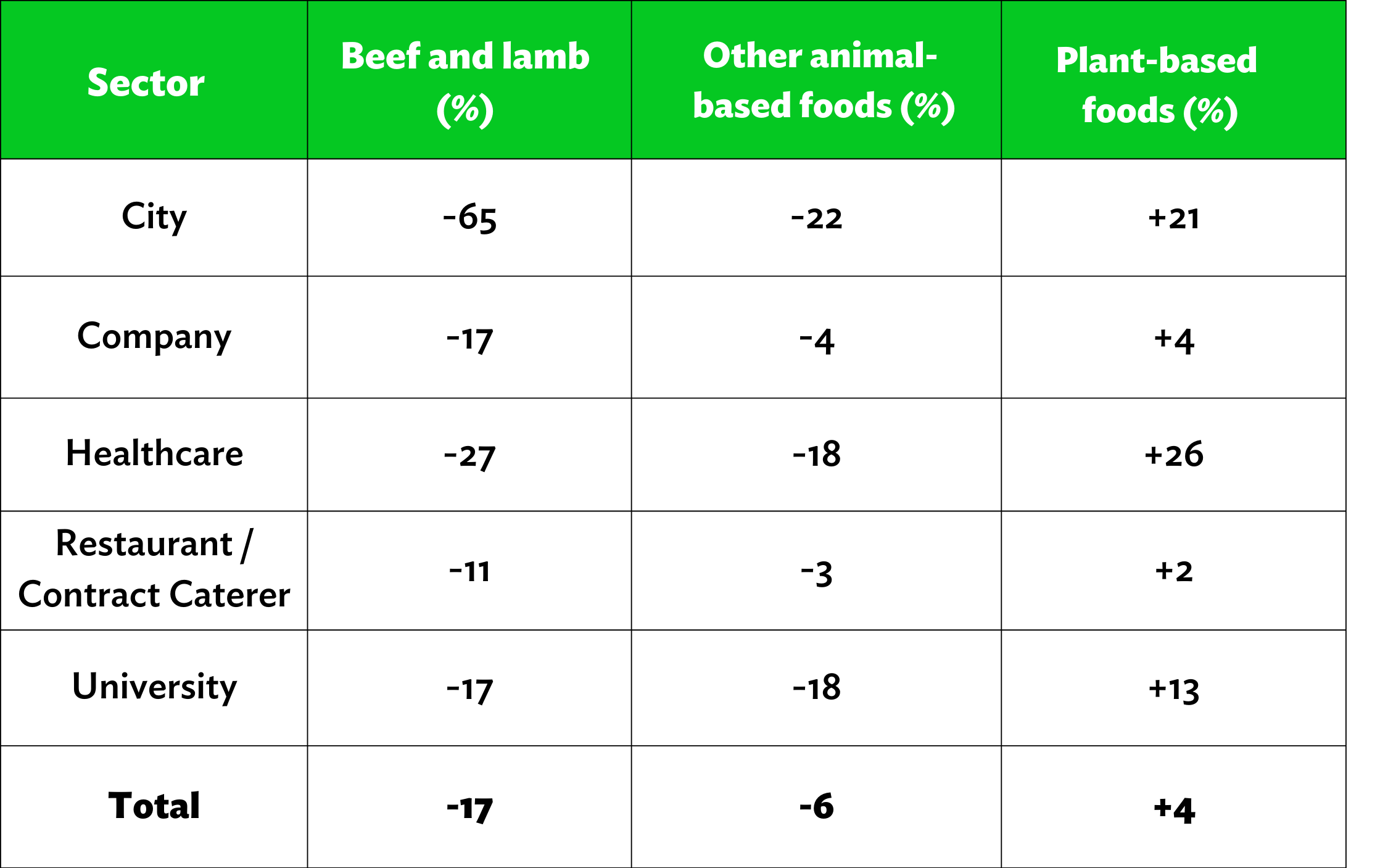

Cities are continuing to make progress far ahead of the pace needed for 2030, which is a 20.3% reduction in per-plate emissions through 2023, and health care facilities are right on track.[6] This drop in emissions has largely resulted from serving less animal-based foods — especially beef and lamb — and serving more plant-based foods (Table 2). For example, cities have decreased the average share of beef and lamb on their plates by 65% and have decreased the average share of other animal-based foods on their plates by 22%. At the same time, cities have increased the share of plant-based foods on the average plate by 21% (Table 2). Together, these changes have reduced overall per-plate emissions for cities by 40%, exceeding the 2030 target in 2023. (Table 1). With these changes, Copenhagen, Ghent, Milan, and New York have already achieved the 2030 target (25%) for absolute emissions reduction, and they are leading the charge on reducing emissions per plate as well.

Table 2: Changes in the share of food types on the average plate by weight (kilograms) through 2023

Note: Trends shown for members who joined Coolfood prior to 2023.

Source: Member data.

As food businesses have bounced back, absolute emissions have rebounded

Although looking at per-plate emissions shows encouraging progress over the past few difficult years for food service, it’s also important to consider total (absolute) emissions. Because the COVID-19 pandemic led many people to avoid eating outside their homes, Coolfood Pledge members’ food purchases were low in 2020 and 2021, which resulted in artificially large dips in their absolute food-related emissions. In 2022 and again in 2023, we saw these numbers rebound as food purchases increased. In some cases, members have also grown their food service operations, meaning they are serving more meals in 2023 than they did before the pandemic.

Overall, the group reduced absolute emissions by 16% between the base year and 2023.[7] This reduction occurred in part due to a 5% decrease in total food purchased (by weight) and was also driven by a 12% decline in total purchases by weight of animal-based foods in 2023, relative to the base year. The reduction in absolute emissions, despite the rebound in total food purchases, reflects the purchasing shifts that drove reductions in the per-plate emissions.

The cohort has made good progress to reduce food-related emissions, with the 16% absolute emissions reduction just ahead of the pace needed for the 2030 target; a reduction of 13.3% through 2023 was necessary to be on track.[8] However, given that trends have shown increasing absolute emissions since 2020-21, it will be important for these recent trends to reverse. Absolute emissions will need to decrease in 2024 and beyond to remain on track.

We estimate that the total food-related carbon emissions costs of these members were 17,156,777 tCO2e in 2023, including 3,786,699 tCO2e from agricultural supply chains and 13,370,078 tCO2e from annualized carbon opportunity costs.[9] Among members who joined before 2023, animal-based foods accounted for 81% of their total food-based GHG emissions in 2023 — with beef and lamb alone accounting for 49% — and plant-based foods accounted for 19% of emissions (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Changes in Coolfood Pledge members’ absolute GHG emissions through 2023

Coolfood’s newest members

As of this writing, 22 members have joined the Coolfood Pledge in 2023-24. We report their figures separately because they have not yet had sufficient time to implement changes and see resulting emissions reductions. We estimate that the total food-related carbon costs of these members were 345,311 tCO2e in 2023, including 75,210 tCO2e from agricultural supply chains and 270,101 tCO2e from annualized carbon opportunity costs.

The newest members of the Coolfood Pledge serve 40 million meals each year. They will need to change their food procurement immediately as they work to reduce their per-plate emissions to get on track for 2030.

Tracking individual member progress

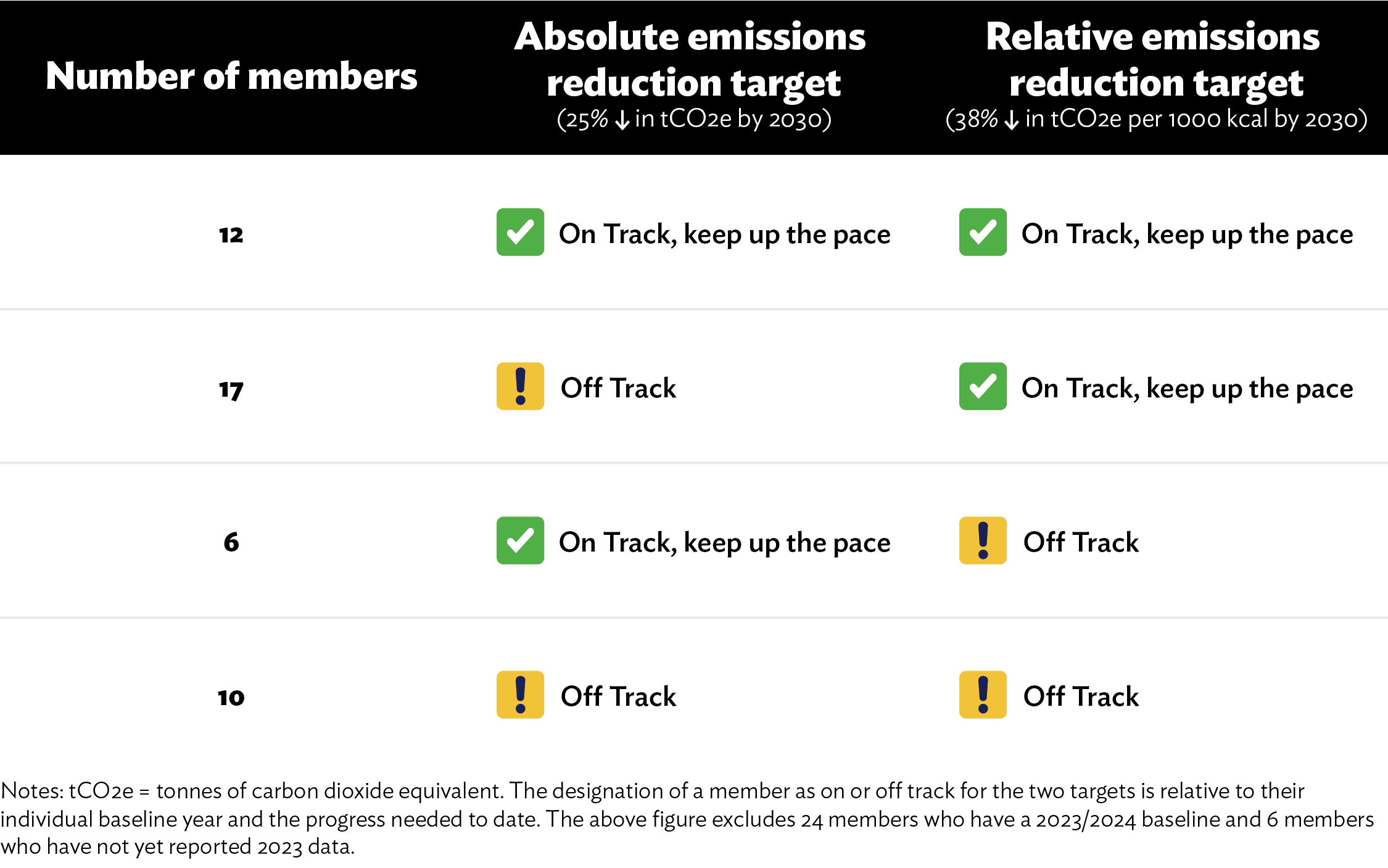

The above metrics track Coolfood Pledge progress across all members, reflecting progress at the sector and cohort level. However, on an individual level, members’ progress is more varied. Table 3 below shows how Pledge members are on or off track for the absolute emissions reduction target and the relative emissions reduction target.

Notably, of the 45 Pledge members with available data, 38% are off track for the absolute target but on track for the relative reduction target. This indicates that they are making progress on serving lower-carbon foods; however, due to increased business volume, they are serving more food overall, thus increasing their absolute emissions. In this situation, the relative reduction target is particularly useful because it allows members to determine if they are reducing the GHG emissions associated with their average plate of food, even if absolute emissions have increased because the number of meals served has increased.

Table 3: Individual Pledge member progress status through 2023 against targets

Table 3 shows that the majority of Coolfood Pledge members are off track for at least one target, and 10 members are off track for both targets. It will be essential for members to accelerate their progress and take decisive action to shift the food they serve. With just five years until 2030, Coolfood recommends that members take the following steps:

- Review procurement data to identify hot spots and opportunities to reduce the purchasing of the most resource-intensive foods. Coolfood can assist members in reviewing their climate impact of food reports and highlight areas of opportunity. Learn how others in your sector have started their journey.

- Set specific annual goals for emissions reductions. Coolfood offers bespoke modeling services to help members get on track and understand the necessary shifts to make for their 2030 goals. Modeling can be customized to account for different lines of business, countries of operation, implementation strategies or growth scenarios.

- Make progress by tapping into behavioral science strategies known to help shift diners toward lower-carbon foods, as outlined in the newly released Food Service Playbook for Promoting Sustainable Food Choices by World Resources Institute. This updated food service playbook offers 18 no-regret techniques for food service operations to implement immediately.

Learn More

More on methods and data sources: Coolfood Pledge technical note

Previous GHG estimates and updates:

[1] For passenger cars in Europe, data from the European Environmental Agency (2020) and Helmers et al. (2019) suggest that the average tailpipe emissions of European cars in 2018 were 1.51 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (tCO2e) per vehicle per year (120.8 gCO2/km * 12,500 km = 1.51 tCO2e)

[2] This report was written by Clara Cho and Raychel Santo. Thanks to Anne Bordier, Gregory Taff and Jillian Holzer for their helpful reviews and to LSF Editorial for copyediting.

[3] In the data year 2022, we reported on progress for members who had joined the Coolfood Pledge prior to 2022. For this report (covering 2023 data), we have updated this cohort to reflect the year of progress made by members who joined the pledge in 2022.

[4] Food-related emissions “per plate” are calculated as food-related emissions per 1,000 kilocalories.

[5] As detailed further in the Coolfood Pledge technical note, global food demand (measured in crop calories) is projected to grow by 21% between 2015 and 2030. Reducing absolute food-related emissions by 25% while accommodating a 21% growth in food demand implies a necessary reduction in emissions per calorie of 38% during that period.

[6] A 38% decline by 2030, relative to 2015, would imply a 20.3% decline would be needed by 2023 assuming linear progress after these first eight years [(38 / 15) * 8 = 20.3].

[7] The base year for the Coolfood GHG reduction target is 2015, but food purchase data from as far back as 2015 were unavailable for most members. We therefore accepted baseline data for any year between 2015 and 2022 for the purposes of establishing a group baseline, as detailed in the Coolfood Pledge technical note.

[8] A 25% decline by 2030, relative to 2015, would imply that a 13.3% decline would be needed by 2023 assuming linear progress in these eight years [(25 / 15) * 8 = 13.3].

[9] Agricultural supply chain emissions include emissions associated with the production of food and animal feed as well as food transport, processing, packaging and food losses prior to the point of purchase (Poore and Nemecek 2018). Carbon opportunity costs are the total historical carbon losses from plants and soils on agricultural lands (this quantity also represents the amount of carbon that could be stored if land in agricultural production were allowed to return to native vegetation) and are annualized as in Searchinger et al. (2018). Carbon opportunity costs are important to include because, as Coolfood members shift their purchases to less land-intensive foods, this metric tracks the climate benefits of using less agricultural land and reducing pressure on the world’s remaining natural ecosystems.